Turkish language

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Turkish Türkçe |

||

|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | IPA: [tyɾktʃe] | |

| Spoken in: | Turkey, Cyprus, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Kosovo, Macedonia, Romania, Serbia and other countries in which Turkish diaspora is present |

|

| Region: | Turkey, Cyprus, Balkans, Caucasus | |

| Total speakers: | ~65 million native, ~75 million total

~10 million as a second language |

|

| Ranking: | 19–22 (native), in a near tie with Italian, Urdu | |

| Language family: | Altaic[1] (controversial) Turkic Southern Turkic or Oghuz Turkish group Turkish |

|

| Writing system: | Latin alphabet (Turkish variant) | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language of: | Turkey, Cyprus, Northern Cyprus, Kosovo, Republic of Macedonia1 1 In municipalities inhabited by a set minimum percentage of speakers |

|

| Regulated by: | Turkish Language Association | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | tr | |

| ISO 639-2: | tur | |

| ISO/FDIS 639-3: | ||

|

Click on the image for the legend |

||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. See IPA chart for English for an English-based pronunciation key. | ||

Turkish (Turkish: Türkçe), a Turkic language, is the mother tongue of the Turkish people native to Turkey. Turkish is also spoken in Cyprus, Bulgaria, Greece, Republic of Macedonia and other countries of the former Ottoman Empire, as well as by several million emigrants in the European Union. The exact number of native speakers in Turkey is uncertain, primarily due to a lack of minority language data.

There is a high degree of mutual intelligibility between Turkish and other Oghuz languages such as Azeri, Turkmen, and Qashqai. If these are counted together as "Turkish", the number of native speakers is 100 million, and the total number including second-language speakers is around 125 million.

Contents |

[edit] Classification

Turkish is a member of the Turkish family of languages, which includes Gagauz and Khorasani Turkish. The Turkish family is a subgroup of the Oghuz languages, themselves a subgroup of the Turkic languages, which some linguists believe to be a part of the Altaic language family.

Like Finnish and Hungarian, Turkish has vowel harmony, is agglutinative and has no grammatical gender. The basic word order is Subject Object Verb. Turkish has a T-V distinction: second-person plural forms can be used for individuals as a sign of respect.

[edit] Geographic distribution

- See also: Turkish diaspora

Turkish is spoken in Turkey and by minorities in 35 other countries. In particular, Turkish is used in countries that formerly (in whole or part) belonged to the Ottoman Empire, such as Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, the Republic of Macedonia, Syria, Greece (especially in Western Thrace) and Israel (by Turkish Jews). More than two million Turkish speaking people live in Germany, and significant Turkish speaking communities in Austria, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. But due to the desegregation of the Turkish immigrants into the country where they immigrated to, not every ethnic Turkish immigrant speaks the language as well as a native Turk would speak it.

Turkish is spoken by almost all of Turkey's residents, with Kurdish making up most of the remainder. However, the vast majority of the linguistic minorities in Turkey are bilingual, speaking Turkish as a second language to levels of native fluency.

[edit] Official status

Turkish is the official language of Turkey, and is one of the official languages of Cyprus. It also has official (but not primary) status in several municipalities of Republic of Macedonia, depending on the concentration of Turkish-speaking local population as well as the Prizren District of Kosovo.

In Turkey, the regulatory body for Turkish is the Turkish Language Association (Turkish: Türk Dil Kurumu - TDK), which was founded by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1932 under the name Türk Dili Tetkik Cemiyeti ("Society for Research on the Turkish Language"). The Turkish Language Association was influenced by the linguistic purism ideology and one of its primary acts was the replacement of loan words and grammatical constructs of Arabic and Persian origin in the language with their Turkish equivalents, which, together with the adoption of the new Turkish alphabet in 1928, shaped the modern Turkish language as it is in use today (see the section on language reform, further below). TDK became an independent body in 1951, with the lifting of the requirement that it should be presided over by the Minister of Education. This status continued until August, 1983, when it was again tied to the government following the military coup of 1980.

[edit] Dialects

As a result of the original nationalist idea of establishing the İstanbul dialect of Turkish as the standard, dialectology remains as a highly immature discipline in Turkey. The standard language of Turkish is essentially the refined Ottoman Turkish language as written in the Latin alphabet but not the initial Arabic alphabet and with the boost of neologisms added and the Arabic and Persian imports excluded. The preferred colloquial form is named İstanbul Türkçesi as manifested in the works of prominent pan-Turkists like Ziya Gökalp (Güzel dil, Türkçe bize / Başka dil, gece bize. / İstanbul konuşması / En saf, en ince bize.) and İsmail Gaspıralı. Academically, Turkish dialects are often referred to as ağız or şive, leading to ambiguity with the linguistic concept of accent. Turkish still lacks a comprehensive atlas of dialects and assimilation into official Turkish is influential.

The main dialects of Turkish include:

- Rumelice (spoken by muhajirs from Rumelia) includes peculiar dialects of Dinler and Adakale,

- Kıbrıs (spoken in Cyprus),

- Edirne (spoken in Edirne),

- Doğu (spoken in Eastern Turkey) has dialect continuum with Azerbaijani in some areas,

- Karadeniz (spoken in the Eastern Black Sea region) is represented primarily by Trabzon dialect,

- Ege (spoken in the Aegean region) has extension to Antalya,

- Güneydoğu (spoken in the South, to the east of Mersin),

- Orta Anadolu (spoken in the Middle Anatolian region),

- Kastamonu (spoken in Kastamonu and vicinity),

- Karamanlıca (spoken in Greece, where it is also named Kαραμανλήδικα) is the literary standard for Karamanlides.

[edit] Sounds

One characteristic feature of Turkish is vowel harmony, meaning that a word will have either front or back vowels, but not both. For example, in vişne "sour cherry" i is closed unround front and e is open unround front. Stress is usually on the last syllable, with the exception of some suffix combinations, and words like masa ['masa]. Also, in the use of proper names, the stress is transferred to the syllable before the last (e.g. Istánbul), although there are exceptions to this (e.g. Ánkara).

[edit] Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p | b | t | d | c | ɟ | k | ɡ | ||||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ||||||||||||||

| Fricatives | f | v | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | ɣ | h | ||||||||

| Affricates | ʧ | ʤ | ||||||||||||||

| Tap | ɾ | |||||||||||||||

| Approximant | j | |||||||||||||||

| Lateral approximants |

ɫ | l | ||||||||||||||

The phoneme /ɣ/ usually referred to as "soft g"(yumuşak g), "ğ" in Turkish orthography, actually represents a rather weak front-velar or palatal approximant between front vowels. It never occurs at the beginning of a word, but always follows a vowel. When word-final or preceding another consonant, it lengthens the preceding vowel.

[edit] Vowels

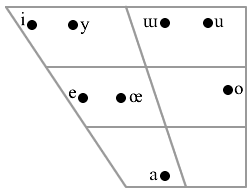

| IPA chart for Turkish monophthongs |

|---|

|

The vowels of the Turkish language are, in their alphabetical order, a, e, ı, i, o, ö, u, ü. There are no diphthongs in Turkish and when two vowels come together, which occurs rarely and only with loanwords, each vowel retains its individual sound.

| Vowel sound | Example | |||

| IPA | Description | IPA | Orthography | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| monophthongs | ||||

| i | Close front unrounded vowel | dil | dil | 'tongue', 'language' |

| y | Close front rounded vowel | ɟy'neʃ | güneş | 'sun' |

| ɯ | Close back unrounded vowel | ɯˈɫɯk | ılık | 'mild' |

| e | Close-mid front unrounded vowel | je̞l | yel | 'wind' |

| œ | Open-mid front rounded vowel | ɟœɾ | gör | 'to see' |

| a | Open front unrounded vowel | dal | dal | 'branch' |

| o | Close-mid back rounded vowel | jol | yol | 'way' |

| u | Close back rounded vowel | utʃak | uçak | 'airplane' |

[edit] Grammar

Turkish is an agglutinative language and as such has an abundance of suffixes, but no native prefixes (apart from the reduplicating intensifier prefix as in beyaz="white", bembeyaz="very white", sıcak="hot", sımsıcak="very hot"). One word can have many suffixes and these can also be used to create new words (like creating a verb from a noun, or a noun from a verbal root, see Vocabulary section further below) or to indicate the grammatical function of the word.

[edit] Nouns and adjectives

Turkish nouns can take endings indicating the person of a possessor. They can take case-endings, as in Latin. There are six noun cases in the Turkish declension system:

- Nominative

- Genitive, formed by adding -ın, -in, -un or -ün, according to the vowel harmony

- Dative, formed by adding -a or -e, according to the vowel harmony

- Accusative, formed by adding -ı, -i, -u or -ü, according to the vowel harmony

- Ablative, formed by adding -den or -dan, according to the vowel harmony

- Locative, formed by adding -de or -da, according to the vowel harmony

- Instrumental. There is also a very common practice of adding the postposition ile, meaning with, as a suffix to the end of nouns (-le or -la, again according to the vowel harmony) which could be treated as an instrumental case.

Taking gün (day) as an example:

| Turkish | English | Noun case |

|---|---|---|

| gün | day, or the day | Nominative |

| günün | a day's, the day's, of the day | Genitive |

| güne | to the day | Dative |

| günü | the day | Accusative |

| günden | of the day, or from the day | Ablative |

| günde | in the day | Locative |

| günle | with the day | Instrumental |

The series of case-endings is the same for every noun, selecting the suffix complying with the vowel harmony. The initial consonant of the suffixes for the ablative and locative cases can also vary depending on the last consonant of the noun being voiced or unvoiced, such as having hava (air) + -da (locative suffix) = havada (in the air), but, ağaç (tree) + -da (locative suffix) = ağaçta (on the tree), instead of ağaçda.

Additionally, nouns can take endings that give them a person and make them into sentences:

|

|

It is often cited that the longest Turkish word ever formed was "Çekoslavakyalılaştıramadıklarımızdan mısınız?" which literally means "are you one of the people whom we could not get resembled as a citizen of Czechoslovakia".

Turkish adjectives as such are not declined (though they can generally be used as nouns, in which case they are declined). Used attributively, they precede the nouns they modify.

Possession is expressed by means of constructions based on verbs meaning "to exist" and "to not exist". Thus, while "var" and "yok" represent "exists" and "not exists," "vardı" and "yoktu" are the preterite of these, while "olacak" and "olmayacak" are the future. These lead to the most bizarre-looking (to a Western reader) sentential structures: e.g., in order to say, "My cat had no shoes," we form:

- kedi + -m + -in ayak + kab(ı) + -lar + -ı yok + -tu

- (kedimin ayakkabıları yoktu)

which literally translates as, "cat-mine-of foot-cover(of)-plural-his non-existent-was."

[edit] Verbs

Turkish verbs exhibit person. They can be made negative or impotential; they can also be made potential. Finally, Turkish verbs exhibit various distinctions of tense, mood, and aspect: a verb can be progressive, necessitative, aorist, future, inferential, present, past, conditional, imperative, or optative.

| Turkish | English |

|---|---|

| gel- | (to) come |

| gelme- | not (to) come |

| geleme- | not (to) be able to come |

| gelebil- | (to) be able to come |

| Gelememiş | She (or he) was apparently unable to come. |

| Gelememişti | She had not been able to come. |

| Gelememiştiniz | You (plural) had not been able to come. |

| Gelememiş miydiniz? | Have you (plural) not been able to come? |

All Turkish verbs are conjugated the same way, except for the irregular and defective verb i- (see Turkish copula), which can be used in compound forms (the shortened form is called an enclitic):

- Gelememişti = Gelememiş idi = Gelememiş + i- + -di

[edit] Vowel harmony

- For more details on this topic, see Vowel harmony.

"Vowel harmony" is the principle by which a native Turkish word generally incorporates either exclusively back vowels (a, ı, o, u) or exclusively front vowels (e, i, ö, ü). As such, a notation for a Turkish suffix such as -den means either -dan or -den, whichever promotes vowel harmony; a notation such as -iniz means either -ınız, -iniz, -unuz, or -ünüz, again with vowel harmony constituting the deciding factor.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | Unrounded | Rounded | |

| High | i | ü | ı | u |

| Low | e | ö | a | o |

The Turkish vowel harmony system can be considered as being 2-dimensional, where vowels are characterised by two features: [front / back] and [rounded / unrounded] (see the table).

[edit] Front/back harmony

Turkish has two classes of vowels — front and back. Vowel harmony states that words may not contain both front and back vowels. Therefore, most grammatical suffixes come in front and back forms, e.g. Türkiye'de "in Turkey" but kapıda "at the door".

[edit] Rounding harmony

In addition, there is a secondary rule that i and ı tend to become ü and u respectively after rounded vowels, so certain suffixes have additional forms. This gives constructions such as Türkiye'dir "it is Turkey", kapıdır "it is the door", but gündür "it is day", paltodur "it is the coat".

[edit] Exceptions

Compound words are considered separate words with respect to vowel harmony: vowels do not have to harmonize between members of the compound (thus forms like bu|gün "today" are permissible). In addition, vowel harmony does not apply for loanwords and some invariant suffixes (such as -iyor); there are also a few native Turkish words that do not follow the rule (such as anne "mother"). In such words suffixes harmonize with the final vowel; thus İstanbul'dur "it is İstanbul".

[edit] Word order

Word order in Turkish is generally Subject Object Verb, as in Japanese and Latin, but not English. A demonstration of this can be seen in the following sentence from a newspaper (Cumhuriyet, 16 August 2005, p. 1). The sentence uses all noun cases except the genitive:

- Türkiye'de modayı gazete sayfalarına taşıyan,

- gazetemiz yazarlarından N. S. yaşamını yitirdi:

| Turkish | English | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Türkiye'de | in Turkey | locative |

| modayı | fashion | accusative of moda |

| gazete | newspaper | nominative |

| sayfalarına | to its pages | dative; sayfa (page), sayfalar (pages), sayfaları (its pages) |

| taşıyan, | carrying | present participle of taşı- |

| gazetemiz | our newspaper | nominative; gazete (newspaper) |

| yazarlarından | from its writers | ablative; yazar (writer) |

| N. S. | [person's name] | nominative |

| yaşamını | her life | accusative; yaşam (life) |

| yitirdi. | lost | past tense of yitir- (lose) from yit- (be lost) |

Which ultimately translates to:

- "One of the writers of our newspaper, N. S.,

- who brought fashion to newspaper pages in Turkey, lost her life."

[edit] Vocabulary

Turkish extensively utilizes its agglutinative nature to form new words from former nouns and verbal roots. The majority of the Turkish words originate from the application of derivative suffixes to a relatively small set of core vocabulary.

An example set of words derived agglutinatively from a substantive root:

| Turkish | Parts | English | Word class |

|---|---|---|---|

| göz | göz | eye | Noun |

| gözlük | göz + -lük | eyeglasses | Noun |

| gözlükçü | göz + -lük + -çü | someone who sells eyeglasses | Noun |

| gözlükçülük | göz + -lük + -çü + -lük | the business of selling eyeglasses | Noun |

| gözlüklenmek | göz + -lük + -len + -mek | becoming an eyeglasses owner | Verb |

| gözlem | göz + -lem | observation | Noun |

| gözlemek | göz + -le + -mek | to observe | Verb |

| gözlemci | göz + -lem + -ci | observer | Noun |

Another example starting from a verbal root:

| Turkish | Parts | English | Word class |

|---|---|---|---|

| yat- | yat- | to lie down | Verb |

| yatık | yat- + -ık | laid, leaned | Adjective |

| yatır- | yat- + -ır- | to lay down (that is, to cause to lie down) | Verb |

| yatırım | yat- + -ır- + -ım | instance of laying down: deposit, investment | Noun |

| yatırımsız | yat- + -ır- + -ım + -sız | without an investment | Adjective |

| yatırımcı | yat- + -ır- + -ım + -cı | depositor, investor | Noun |

New words are also frequently formed by compounding two existing words into a new one (like in German). A few examples of compound words are given below:

| Turkish | English | Constituent words | Literal meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pazartesi | Monday | Pazar (Sunday) and ertesi (after) | After Sunday |

| bilgisayar | computer | bilgi (information) and say- (to count) | Information counter |

| gökdelen | skyscraper | gök (sky) and del- (to pierce) | Sky piercer |

| başparmak | thumb | baş (prime) and parmak (finger) | Primary finger |

[edit] Language reform

- For more details on this topic, see Ottoman Turkish language.

After the adoption of Islam by the Ottomans as their religion, Ottoman language acquired a rather large collection of loan words from Arabic and Persian, consecutively influencing Turkish. Turkish literature during the Ottoman period, in particular Ottoman Divan poetry was heavily influenced by Persian forms, including the adoption of Persian poetic meters and ultimately the bringing of Persian words into the language in great numbers. During the course of over six hundred years of the Ottoman Empire, the literary and official language of the empire was a mixture of Turkish, Persian and Arabic, which differed considerably from everyday spoken Turkish of the time, and is now given the name Ottoman Turkish.

After the foundation of the Republic of Turkey, the Turkish Language Association (Turkish: Türk Dil Kurumu - TDK) was established by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1923 with the aim of conducting research on Turkish language. One of the tasks of the newly established association was to replace loan words of Arabic and Persian origin in the language with Turkish equivalents. The language reform was a part of the ongoing cultural reforms of the time (which were in turn a part in the broader framework of Atatürk's Reforms) and also included the abolishment of Arabic script in lieu of the new Turkish alphabet derived from the Latin alphabet (see the writing system section below) which greatly helped increasing the literacy rate of the population. By banning the usage of replaced loan words in the press, the association succeeded in removing several hundred Arabic words from the language. While most of the words introduced to the language by TDK were new, TDK also suggested using old Turkish words which had not been used in the language for centuries.

Older and younger people in Turkey tend to express themselves with a different vocabulary due to this sudden change in the language. While the generations born before the 1940s tend to use the old Arabic origin words, the younger generations favor using new expressions. Some new words are not used as often as their old counterparts or have failed to convey the intrinsic meanings of their old equivalents. There is also a political significance to the old versus new debate in the Turkish language. Sectors of the population that are more religious also tend to use older words in the press or daily language. Therefore, the use of the Turkish language is also indicative of adoption/resistance to Atatürk's reforms which took place more than 70 years ago. The last few decades saw the continuing work of the Turkish Language Association to coin new Turkish words to account for new concepts / technologies as they enter the language as loan words (mostly from English), but the association is occasionally criticized for coining words that obviously seem and sound as "invented".

However, many of the words derived by TDK, live together with their old counterparts. The different words –one originating from Old Turkic or derived by TDK and one borrowed from Arabic, Persian, or one of the European languages, especially French- having exactly the same literal meaning are used to express slightly different meanings, especially when speaking about abstract subjects. This is quite like the usage of Germanic words and the words originated from Romance languages in English.

Among some of the old words that were replaced are terms in geometry, directions (north, south, east, west), some of the months' names and many nouns and adjectives. Many new words have been derived from Old Turkic verb roots. Some examples of modern Turkish words and their old counterparts are:

| Ottoman Turkish word | Modern Turkish word | English meaning | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| müselles | üçgen | triangle | derived from the noun üç, which means "three" |

| tayyare | uçak | airplane | derived from the verb uçmak, which means "to fly" |

| nispet | oran | ratio | the old word is still used in the language today together with the new one |

| şimal | kuzey | north | derived from the Old Turkic noun kuz, which means “cold and dark place” |

| Teşrini-evvel | Ekim | October | the noun ekim means “the action of planting”, referring to the planting of cereal seeds in autumn, which is widespread in Turkey |

Please see List of replaced loan words in Turkish for an extensive list of replaced and current loan words

[edit] Writing system

Turkish is written using the Turkish alphabet, a modified version of the Latin alphabet, which was introduced in 1928 by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk as an important step in the cultural reforms of the period, replacing the Ottoman Turkish alphabet previously in use. The work of preparing the new alphabet and selecting the necessary modifications to account for sounds specific to Turkish language, was appointed to the Dil Encümeni (Language Commission) including Falih Rıfkı Atay, Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu, Ruşen Eşref Ünaydın, Ahmet Cevat Emre, Ragıp Hulûsi Özdem, Fazıl Ahmet Aykaç, Mehmet Emin Erişirgil and İhsan Sungu. The introduction of the new Turkish alphabet was supported by Public Education Centers opened throughout the country, cooperation with publishing companies, and encouragement by Atatürk himself in trips to the countryside teaching the new letters to the public.

The sounds of the individual letters exhibit few surprises for English speakers. Following International Phonetic Alphabet conventions on phonetic transcription, angle brackets < > here are used to enclose written letters, and brackets [ ] are used to enclose symbols that represent the sounds. Most writing-sound correspondences can be predicted by English speakers, with the following exceptions. The <c> is pronounced [dʒ], like <j> in jail. The <ç> is pronounced [tʃ] like the <ch> in church. The <j> represents [ʒ] and is pronounced like the <s> in pleasure. The <ş> represents [ʃ] and is pronounced like <sh> in sheet. The <ı> represents [ɨ], a sound which does not exist in most varieties of English. It is pronounced somewhat like the <o> in button or the <e> in munificent but with the mouth more closed and raised in the center. The <ğ> is pronounced like a soft, voiced version of the guttural Scottish <ch> or merely manifested by lengthening the precedent vowel and assimilating any subsequent vowel (e.g., soğuk is pronounced [souk], rather like soak in English)—except for the two highly irregularly spelled verbs döğmek and öğmek, where <ğ> is pronounced [v].

The effect of Atatürk's introduction of an adapted Roman alphabet was a dramatic increase in literacy from Third World levels to nearly one hundred percent. It is critical to note that, for the first time, Turkish had an alphabet that was actually suited to the sounds of the language; the Arabic alphabet, which was hitherto in use, commonly shows only three different values for vowels (the consonants waw and yud, atop which the long 'u' and 'i' sounds, respectively, are occasionally multiplexed, and the alif, which can carry long medial 'a' or any initial vowel) but also lacked several vital consonants. The lack of discrimination among vowels is serviceable in Arabic (which sports few vowel sounds to begin with) but intolerable in Turkish, which features eight fundamental vowel sounds and a host of diphthongs based thereupon.

[edit] The language in daily life

Turkish has many formulaic expressions for various social situations. Several of them feature Arabic verbal nouns together with the Turkish verb et- ("make, do").

| literal translation | meaning (if different) | |

|---|---|---|

| Merhaba | Welcome | Hello |

| Alo | Hello (from French "allô") | (on the telephone: Hello or Are you still there?) |

| Efendim | My lord | 1. Hello (answering the telephone); 2. Sir/Madam (a polite way to address any person, male or female, married or single); 3. Excuse me, could you say that again? |

| Günaydın | [The] day [is] bright | Good morning |

| İyi günler | Good days | Good day |

| İyi akşamlar | Good evenings | Good evening |

| İyi geceler | Good nights | Good night |

| Evet | Yes | |

| Hayır | No | |

| Belki | Maybe | |

| Hoş geldiniz | You came well / pleasantly | Welcome |

| Hoş bulduk | We found [it] well | We are (or I am) glad to be here |

| Nasılsın? | How are you (sing.)? | How are you? (familiar) |

| Nasılsınız? | How are you (pl.)? | How are you? (respectful, or plural) |

| İyiyim; siz nasılsınız? | I'm fine; how are you? | |

| Ben de iyiyim | I too am fine | I am fine too |

| Affedersiniz | You make [a] forgiving | Excuse me |

| Lütfen | Of favour | Please |

| Teşekkür ederim; Sağolun | I make [a] thanking; Be alive | Thank you |

| Bir şey değil | It is nothing | You're welcome |

| Rica ederim | I make [a] request | Don't mention it; You're welcome; Don't say such bad things of yourself; Don't say such good things of me |

| Estağfurullah | I seek God's forgiveness (common Muslim prayer) | (similar to rica ederim) |

| Geçmiş olsun | May [it] be passed | Get well soon (said to somebody in any kind of difficulty, not just sickness; or to somebody who has just come through difficulty) |

| Başınız sağ olsun | May your head be healthy | My Condolences (said to somebody in mourning) |

| Elinize sağlık | Health to your hand | (said to praise the person that made this delicious food or other good thing) |

| Afiyet olsun | May [it] be healthy | bon appétit (good appetite) |

| Kolay gelsin | May [it] come easy | (said to somebody working) |

| Güle güle kullanın | Use [it] smiling | (said to somebody with a new possession) |

| Sıhhatler olsun | May [it] be healthy | (said to somebody who has bathed or had a shave or haircut) |

| Hoşça kal(ın) | Stay nice | "So long" or "Cheerio" (said to the person staying behind) |

| Güle güle | [Go] smiling | Good bye (said to somebody departing) |

| Allah'a ısmarladık | We commended [you] to God | Good bye [said to the person staying behind(for a long time)] or Adieu in French |

A famous quotation and motto of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk:

- Yurtta sulh, cihanda sulh "Peace at home, peace in the world."

In the current language, this is

- Yurtta barış, dünyada barış.

[edit] Notes

- ^ "

Ethnologue"

[edit] References

- Geoffrey Lewis (2001). Turkish Grammar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-870036-9.

- İsmet Zeki Eyuboğlu (1991). Türk Dilinin Etimoloji Sözlüğü [Etymological Dictionary of the Turkish Language]. Sosyal Yayınları, İstanbul. ISBN 975-7384-72-2.

- Sevgi Özel, Haldun Özel, and Ali Püsküllüoğlu, eds. (1986). Atatürk'ün Türk Dil Kurumu ve Sonrası [Atatürk's Turkish Language Society and After]. Bilgi Yayınevi, Ankara.

- Ali Püsküllüoğlu (2004). Arkadaş Türkçe Sözlük [Arkadaş Turkish Dictionary]. Arkadaş Yayınevi, Ankara. ISBN 975-509-053-3.

- Geoffrey Lewis (2002). The Turkish Language Reform: A Catastrophic Success. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-925669-1.

[edit] See also

- Turkish alphabet

- Turkish literature

- Turkish folk literature

- List of replaced loan words in Turkish

- List of English words of Turkic origin

[edit] External links

- (Turkish)

- (Turkish)

- (Turkish)

|

|

|||

| West Turkic | |||

| Bolgar | Bolgar* | Chuvash | Hunnic* | Khazar* | ||

| Chagatay | Aini2| Chagatay* | Ili Turki | Lop | Uyghur | Uzbek | ||

| Kypchak | Baraba | Bashkir | Crimean Tatar1 | Cuman* | Karachay-Balkar | Karaim | Karakalpak | Kazakh | Kipchak* | Krymchak | Kumyk | Nogay | Tatar | Urum1 | ||

| Oghuz | Afshar | Azerbaijani | Crimean Tatar1 | Gagauz | Khorasani Turkish | Ottoman Turkish* | Pecheneg* | Qashqai | Salar | Turkish | Turkmen | Urum1 | ||

| East Turkic | |||

| Khalaj | Khalaj | ||

| Kyrgyz-Kypchak | Altay | Kyrgyz | ||

| Uyghur | Chulym | Dolgan | Fuyü Gïrgïs | Khakas | Northern Altay | Shor | Tofa | Tuvan | Western Yugur | Sakha / Yakut | ||

| Old Turkic* | |||

| Notes: 1 Listed in more than one group, 2 Mixed language, * Extinct | |||